Feminism and Restorative Justice are natural allies. Here’s why.

I’ve been working in feminist spaces for nearly two decades, and I’ve witnessed the unwavering passion and commitment of advocates striving for a more equitable world. The feminist movement has achieved significant progress, but I’ve also felt the constraints of systemic barriers holding us back.

Too often, we find ourselves in an echo chamber. We navigate incremental wins while grappling with an approach so cautious that it resists significant disruption to the status quo. It’s precisely in this challenging space — where the movement’s drive for change meets resistance — that the power of a decolonised, Restorative Justice-informed approach to feminism can be tapped into. Feminism has long aimed to dismantle inequitable systems and uplift women. But it has often struggled to be fully inclusive, collaborative and transformative in its efforts.

This is where Restorative Justice comes in — it offers a framework for true accountability, healing and collaboration. It offers the opportunity for movements like feminism to become more inclusive and intersectional. My academic work on decolonised Restorative Justice and my professional experience in the social justice sector (currently as Director of Advocacy and Communications at Comotion) has only affirmed this.

When grounded in real intention, Restorative Justice has the power to drive meaningful and lasting change that can transform larger social movements including feminism.

That’s exactly why I was so honoured to deliver the annual lecture of the International Journal of Restorative Justice at World Mediation Forum XII earlier this month. To join a community of thinkers and practitioners who see Restorative Justice as a way of life, not just a practice.

What is Restorative Justice all about?

In my first book, Decolonising Restorative Justice: A Case of Policy Reform, I critically analyse Restorative Justice policy in Jamaica, exploring how intention, process and context shape policymaking. I introduce the concept of “opportunistic policy transfer,” where a government adopts policies from another country not out of a genuine commitment to justice reform — but to meet international standards and gain donor support.

Restorative justice is a philosophy and set of practices aimed at repairing harm caused by wrongdoing. It seeks to restore relationships and reintegrate individuals back into society.

With an RJ approach, those affected by the harm — victims, offenders and the community alike — come together to discuss the impact of the wrongdoing, understand the reasons behind it and work collaboratively on a plan to repair the damage. This might include apologies, restitution or other forms of restitution that help both the victim and offender heal.

At its core, Restorative Justice is about accountability and dialogue, and aims to bring about long-lasting resolutions that go beyond punitive measures. It’s often used in cases of crime, but the principles can also apply to broader social contexts, including movements for justice and equality.

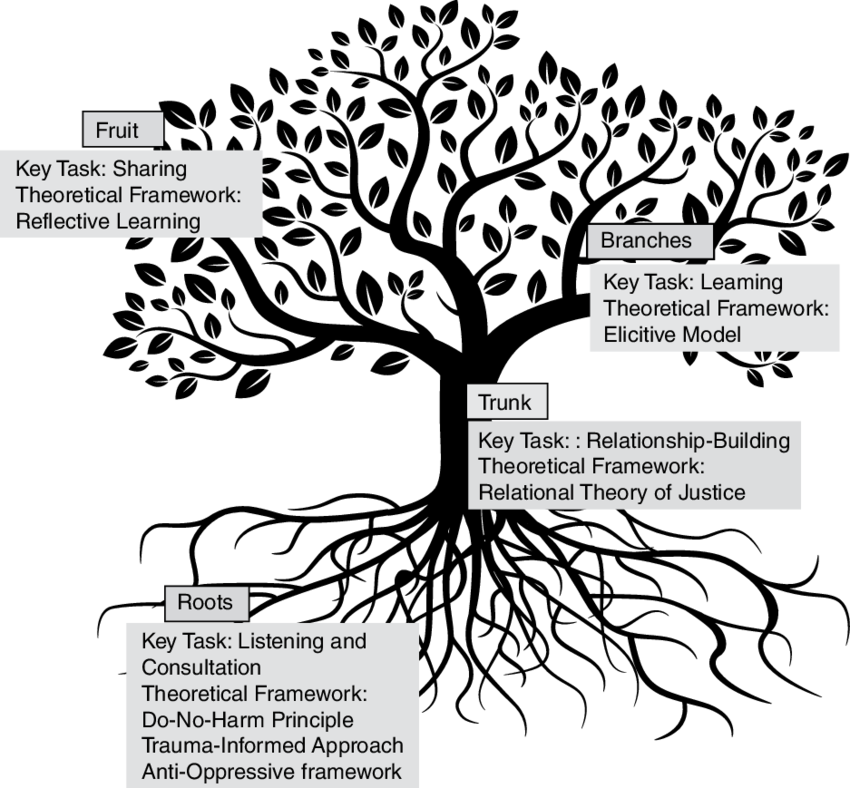

Meaningful Restorative Justice is not pre-packaged; it is truly responsive to people’s needs, as can be seen in Asadullah’s decolonisation tree.

It is this decolonised version of Restorative Justice that holds valuable lessons for feminist movements. This model necessitates reimagining justice, rather than merely refining or complementing the existing frameworks.

Here, decolonisation is an ongoing, transformative journey focused on creating systems based on equity and mutual respect. Similar to colonised Restorative Justice, the limitation of feminism stems in part from a lack of meaningful intention from its inception, as highlighted by exclusions in the movement.

What are the exclusions in mainstream feminism?

Mainstream feminism has largely served a narrow demographic — primarily white, cisgender, middle-class women. The neglect of cultural manifestations of power has limited the movement’s effectiveness in terms of its foundational goal of achieving equity for all women.

The Neglect of Intersectionality: The Historical and Ongoing Exclusion of Black Women

The first wave of feminism, emerging in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was rooted mainly in the United Kingdom and the United States and focused on political rights, particularly suffrage. Despite its groundbreaking intentions, this movement largely marginalised Black women.

Anna J. Cooper in her 1892 work ‘A Voice from the South by a Black Woman of the South’, addressed the “double enslavement” of Black women by race and gender.

The second wave of feminism, beginning in the 1960s, focused on issues like sexuality, reproductive rights and equal pay, but again centred the experiences of privileged white women. Black feminists established their own organisations such as the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO). This was so they could address the unique intersections of race, gender and class.

bell hooks later reflected on this exclusion, noting that feminism, while claiming to be “for everybody,” often failed to address the compounded oppressions faced by poor women of colour.

Today, the concept of intersectionality — coined by pioneering critical race theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw — has promoted greater awareness. Black-led movements like the #MeToo Movement and the creation of the Black Feminist Fund mark progress. However, the disparities persist.

Black feminist movements continue to encounter substantial challenges, including limited financial support, with less than 0.5% of philanthropic funding directed toward these efforts — reflecting the broader economic and social inequalities confronting Black women.

While some strides have been made to include Black women in the movement, many feminist spaces still fail to acknowledge the profound and compounding impacts of intersections. This lack of intersectionality alienates potential allies and limits the movement’s capacity to create comprehensive social change.

The Exclusion of Men in Feminist Advocacy

We need to recognise that patriarchy also harms men, so they should have a vested interest in dismantling these structures too. Patriarchy can hold men back by enforcing rigid norms that discourage emotional expression and pressurise them to conform to traditional masculinity.

When men are excluded, the movement’s potential to foster accountability and engage men as allies in combating gender-based violence is significantly limited.

Men are responsible for 98% of reported sexual assaults against women. Additionally, data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics indicates that men are the offenders in more than 90% of all reported rape cases, both against female and male victims.

Further research indicates that up to 86% of male survivors of sexual assault do not disclose their experiences. This underreporting is a double whammy: it affects the individual and reinforces harmful stereotypes around masculinity.

Restorative Justice offers a path towards accountability by encouraging men to acknowledge their wrongdoing and have a direct hand in reconciling that harm. While Restorative Justice focuses on identifying harm and fostering accountability, it also notes that the complex backgrounds shaping harmful behaviours are frequently rooted in social advantage.

Men need to see themselves as part of the solution to gender-based issues, leading to a holistic approach that can dismantle patriarchal systems more effectively.

To embrace collective advocacy, we must create a feminist movement that reflects Restorative Justice values. This type of feminist movement would centre equity through shared ownership and collective action. It would prioritise sustainable collaboration over fleeting victories, honouring each issue as a crucial part of a whole.

I’ll be continuing these reflections in my next article, where I’ll dive into the three key lessons that Restorative Justice can offer the feminist space. Stay tuned!